MLOps course: Introduction

A machine learning model is only useful when it is in production, however, going from Jupyter Notebook to deployment in the production environment (and running reliably) can take more effort than one expects. “Just give the model to the software engineers” is not a very effective solution. The term MLOps (Machine Learning + DevOps) thus describes the processes that bridge this gap. Fittingly, Andrew Ng and the team at DeepLearning.AI has created a Coursera Specialization on this topic, and I was only too quick to take it. Here I want to summarize my takeaways from the first (of the four) course: Introduction to Machine Learning in Production.

The Big Picture

While the greatest and latest ML models or architectures often get the most excitements, putting them into practical use (i.e., used by the intended audience) usually takes much more effort. In reality, there won’t be pristine data handed to you in a reliable fashion, ready for you to call the .predict() method. A lot of things can go wrong, and they will go wrong: missing data, 10 of the 5,000 features suddenly become unavailable, the data is too large to fit in a single machine’s memory, the latency is more than 2 seconds, …, the list goes on and on.

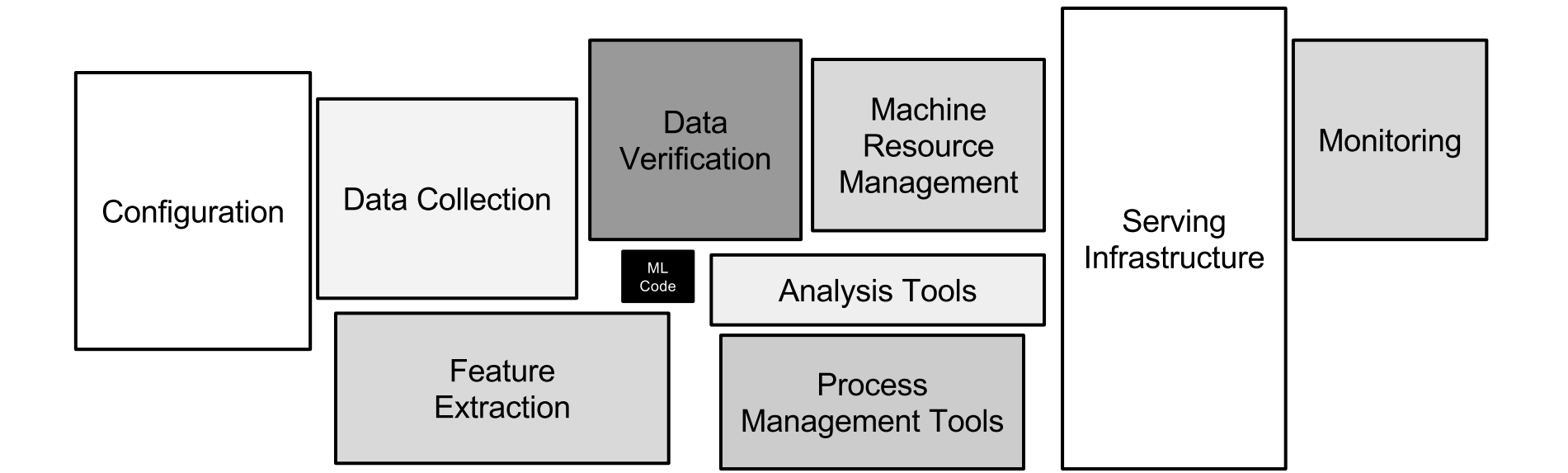

In the grand scheme of things, the ML models only occupy a small portion of the whole ecosystem, which makes the ML models work. The figure below sums up this situation quite succinctly (reference).

The gist of MLOps, therefore, is to build the end-to-end pipelines, so that your greatest and latest ML models can finally see the light of the day.

The ML Project Lifecycle

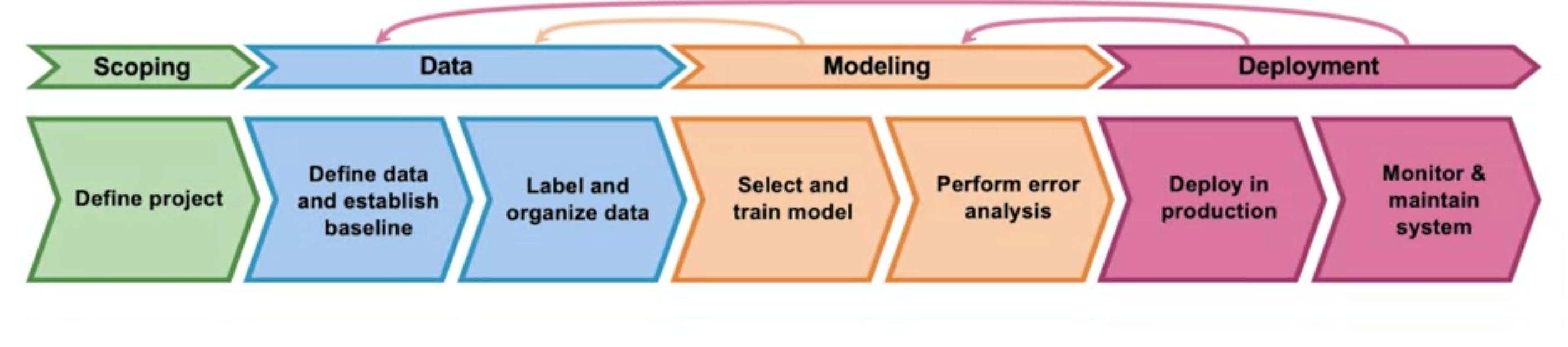

The general pattern (summarized by Andrew Ng and I can’t agree more) is to encapsulate the ML project lifecycle to different components, and define clear interface between different components. Namely, the four components are scoping, data, modeling, deployment (figure screenshot from the course).

Scoping

This might be the least technical component, but can be the most difficult step.

Value of the project. Not all the projects require a deep learning model, and often not even an ML model to start with. There are inevitable costs associated with developing and deploying ML models, and one needs to be convinced that the (long-term) return outweighs the cost.

More importantly, the value of an ML project usually is to improve the business bottom line, i.e, the business metrics. If an ML model achieves out-of-chart technical metrics, but does not move the business needle, it will be hard to get the buy-in from the stakeholders. As such, making good estimations from the technical metrics to the business metrics should be part of this scoping step.

Feasibility of the project. On the other end of the spectrum, there are tasks, neither domain experts nor some sophisticated ML models can seemingly tackle. For example, using the historical stock prices, to predict the future price of that given stock will almost certainly lead to, at best, random guesses. There are people trading stocks for a living (e.g., hedge funds), but their scope won’t be as narrow as a single stock.

Data

An ML model is only as good as its training data. Put it differently, garbage in, garbage out. This step is where a real ML project differs most from a Kaggle competition: we are not only the mere consumer of the data, but also the producer and guardian of the data.

Data quality. The majority of the ML projects deal with labeled data. However, getting the “correct” label might take more effort than one would expect, especially if there are humans involved in making the labels. For example, in object detection problems, different labelers might draw (sometimes drastically) different bounding boxes for the same object. Ensuring the quality of the data (including both features and labels) is a more worthy investment, than the most advanced ML model.

Data pipeline. It is often the case that the training data will accumulate over time (e.g., new clicks on the ads), therefore, a data pipeline is needed to process the influx of data (not necessarily streaming). To this end, one probably needs infrastructure support (e.g., Airflow, Spark, Kafka), and some monitoring guardrails to ensure the quality.

As summarized by Andrew Ng: if one is dealing with small data, then make sure the data, especially the labels, are clean. On the other hand, if one is dealing with big data, then investigate efforts on data processing.

Training

This is the more discussed component in the ML project lifecycle, with which most of the ML practitioners are familiar. One thing I think worth mentioning is, try to establish a model performance baseline early on. This baseline can be either from the previous model, or if one is dealing with a new problem, with a simple model (e.g., linear model). Aiming directly with the latest and greatest model architecture is exciting, but that would usually fail to deliver results in a reasonable time frame.

Another interesting technique mentioned by Andrew Ng is data augmentation. The concept can be understood best in the image classification setting: once you have an image that is classified, e.g., as a “cat image”, then if you flip the image horizontally, it would not change the semantic of the image (hence the label), but effectively that’s a new sample for training. Aside from flipping, once can do offset, rotation, …, you get the idea. This trick might not apply to all ML problems, but keep this in mind and it might come in handy.

Deployment

This part of the ML project lifecycle is, surprisingly, lightly touched in this introductory course. Andrew only covers some generic deployment patterns, that are common in general software development cycles. Examples are shadow deployment (two versions running in parallel but only one is shown), canary deployment (roll out to a small portion of the data/traffic), blue/green deployment (100% switch over but keep both versions alive). In any of the patterns, the capability of rollback to the previous version is of paramount importance.

One key takeaway is that, we need to set up proper monitoring of the deployment pipeline, such that any error can be caught early and prevent them from propagating downstream. In the case of an incident (there will be incidents!), monitors will also help us to quickly identify the root causes.

Conclusion

As always, I truly enjoyed the contents brought by Andrew Ng. There are three more courses in this specialization that cover the data, training, and deployment aspects, respectively. I’m really looking forward to them!

Leave a Comment