Containers and their orchestration

One motto I hold as a data scientist is “the only useful code is production code”. It is a daunting thought for someone like me to write production level code, and it is a more frightening thought to put my codes in production. However, if that is some skill one has to learn to become a more efficient data scientist, then let’s do it.

In the past week, We hosted Jérôme Petazzoni for an excellent 3-day workshop on Kubernetes. Initially, I was a little concerned about how much I could actually learn, given my almost non-existing knowledge in DevOps, but Jérôme crafts a very well-paced syllabus, starting from container basics all the way to some advanced Kubernetes operations, with hands-on session throughout. Each participant is assigned his/her own AWS EC2 and Kubernetes cluster, so that we can always try out we are just taught. The slides are designed in a clean yet informative manner, one can easily come back and review sections that are glossed over.

Why container (Docker)

One of the biggest hurdles between moving your kick-ass algorithm/routine developed on your local laptop (often in the form of a jupyter notebook), and the production environment (i.e., so everyone else can use it) is the “dependency hell”. I once had to debug a model that I trained two years ago, only to realize the pandas version was not compatible with the latest one I have in my current dev environment. It was a gruesome experience to make it finally work. One obvious solution is to take a “snapshot” of the whole dev environment, and duplicate it in the prod environment, so everything will work! Now we are talking along the line of a virtual machine (VM). It would solve the problem all right, but VM can require quite some system resources (CPU, memory, and a full-fledged OS), to serve just the logistic regression model that you spent 5 seconds training. If someone else needs to run his/her applications, another VM will be needed, with more dedicated system resources (CPU, memory, OS, etc). That seems pretty wasteful.

Incomes the container. To solve the dependency hell issue, all one needs is to specify the required packages and their respective versions, together with the codebase. Encapsulate all that essentials as your application, and share the system resources with other applications. Such reductions in system resource can directly translate to financial savings, be it on-premises hardware investment, or cloud-based billings. For more reasons why container is beneficial, check out Chapter 1 of Jérôme’s slides.

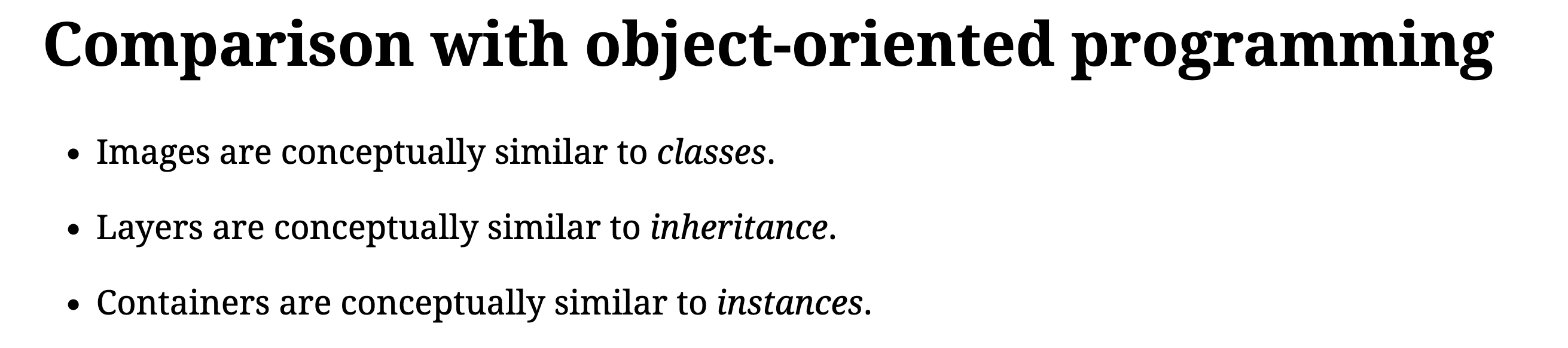

While container as a concept can be general, Docker is the most popular implementation of this concept, to the point it almost becomes synonyms to container. However, there are still some subtle terms, that should be better understood. Before going into the workshop, I found the concepts of container, image, layer quite confusing, until Jérôme showed the following slide, that drives the point home.

If there is anything I learned from the workshop, that will be it.

Why orchestration (Kubernetes)

Jérôme then guided us through more advance container (Docker) concepts such as volume, network, and docker-compose, and also tricks on optimizing images. The focus, however, quickly switched to container orchestration.

At first, I found the emphasis of orchestration pointless: we already have deployed our applications in the production environment, what else do we need? In leading to the reason behind orchestration, Jérôme gave two examples.

The first is the capability to dynamically scale the number of workers (containers) of a website, whose workload changes periodically. The capability to automatically scale the number of workers could easily save the owner a lot of AWS bills.

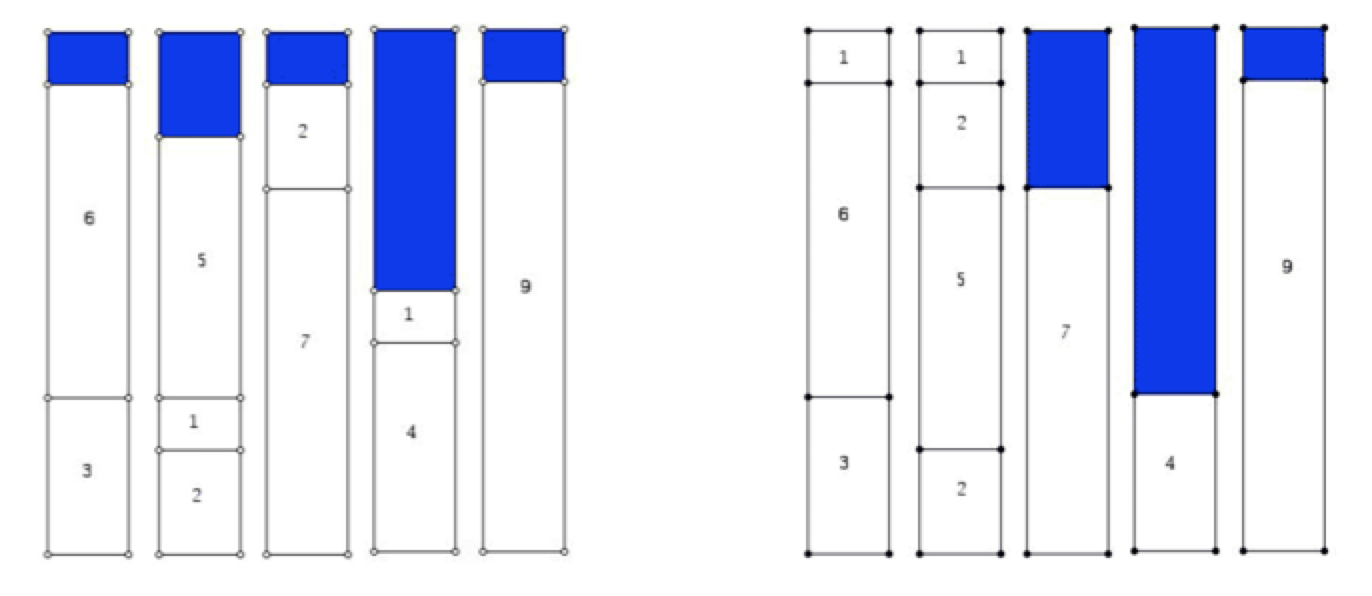

The second example truly convinces me the benefit of orchestration, that is to schedule the system resource for different workloads. Imagining we have a list of jobs to run on 5 servers, each server has 10 GB of RAM, and each job requires different amounts of RAM resource. This resembles a 1D bin-packing problem, and it requires some scheduler (i.e., orchestration) to allocate different jobs on each server. Below we have two of such orchestrations, and one could easily argue that the arrangement on the right is better since it can fit another 6 GB job whereas the left one can not.

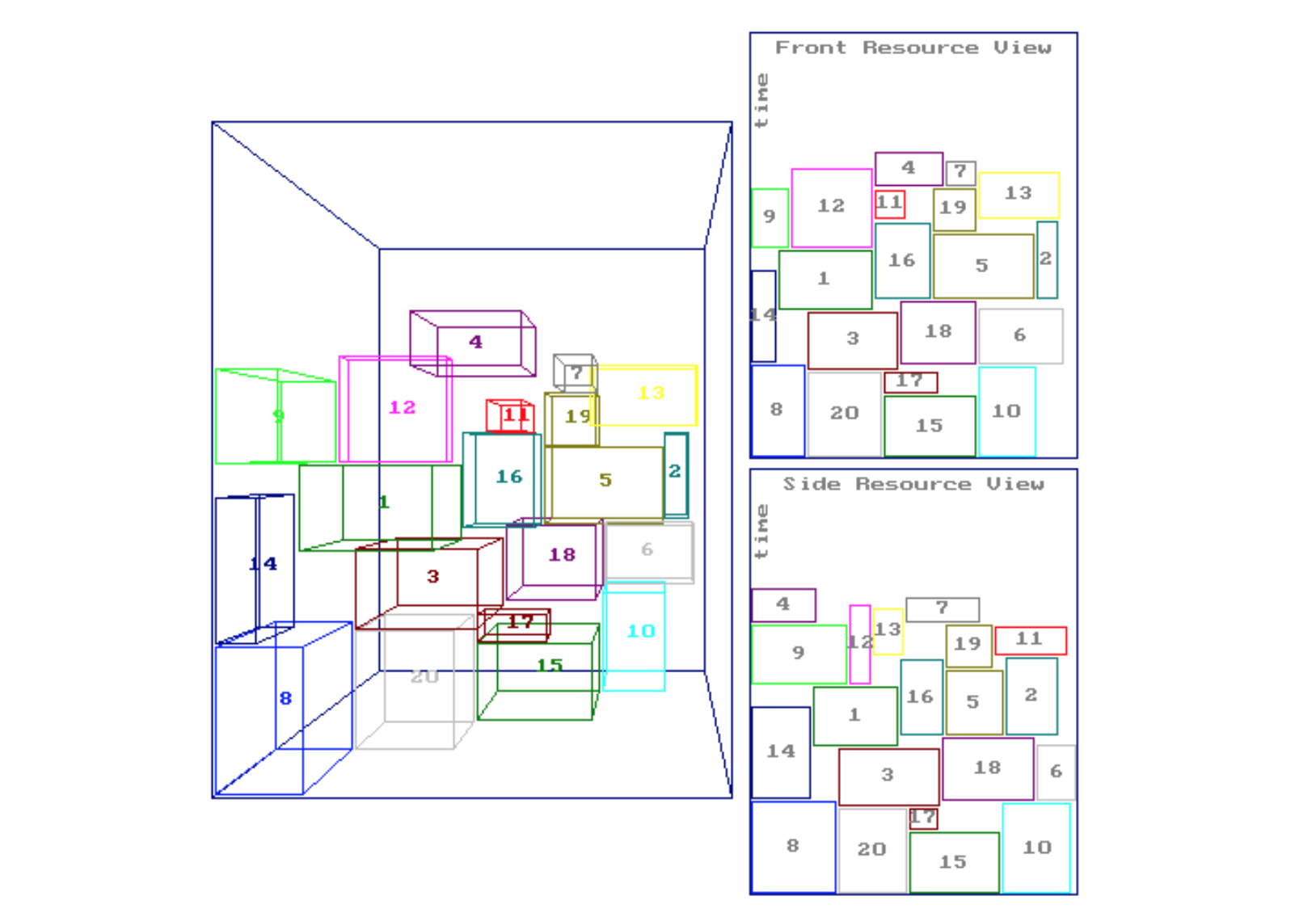

A job is more likely to have more than just one system resource requirement, therefore we quickly move to high dimensional bin-packing problem, such as the 3D case illustrated below. This example alone would persuade me to dive deeper.

Just as Docker is almost synonyms to container, Kubernetes (also knows as k8s) is the name of container orchestration. With k8s overseeing all the services (applications that talk to the outside world), deployments (replica of containers running the same applications without interruption), and volumes (persistent file storages), one can easily manage a complex system (easily only after mastering all the concepts). On top of k8s, there are tools such as Helm to manage k8s, and that was where I was truly lost… I guess I will revisit the slides later.

What is next

Get the hands dirty! I have already containerized some of my projects and deployed them on EC2 instances. That is done without k8s. Luckily WeWork has engineering teams maintaining multiple k8s clusters, and developed an internal k8s package. Can’t wait to use all the knowledge that I just acquired and apply them in real projects!

Leave a Comment