Machine Learning Design Patterns: Reproducibility

It has been a few busy months since I started at Instacart, and finally I can catch some breath during the holiday break. Ruling out the possibility of travel, it allows for more time to read a few books. To this end, I’ve been plowing through this wonderful book: Machine Learning Design Patterns by Valliappa Lakshmanan, Sara Robinson, and Michael Munn. The book is relatively recent, and largely based on (but not necessarily bounded by) Google BigQuery and TensorFlow/Keras frameworks. One thing I truly appreciate about this book is that, it is organized as independent modules, such that for a reasonably adept machine learning (ML) practitioner, one can easily pick up the area of interests and dive in.

I strongly resonate with many of its content and reckon it would be a good idea to summarize the key points, to the very least, for my own future reference. In this post, I will focus on the Reproducibility Design Patterns (Chapter 6 of the book).

Transform

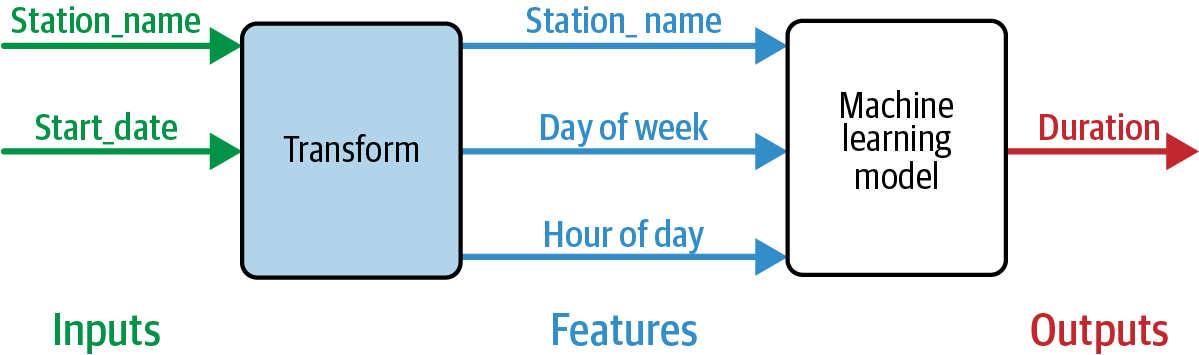

The key idea of this pattern is to separate input, feature, and estimator. As a whole, they consist of what is considered a model, that can be readily put into production. The process that turns input to feature is what we call Transform.

It is very common to preprocess the raw inputs, e.g., transforming them to format/values (features) that are expected by the estimators. Common examples include standardization, min-max scaling (for scalar inputs), one-hot encoding, embedding (for categorical inputs). To ensure reproducibility, it is suggested to include such preprocessing steps as part of the model. With sklearn, one can leverage the Pipeline class, and with TensorFlow/Keras, one can use the tf.feature_column API, to make the preprocessing as part of the computation graph (i.e., model).

The benefit of applying this design pattern is obvious: when put into production, the model will ingest the raw input, whereas the preprocessing steps will be encapsulated, yet they are part of the model. When we deploy a new model, we will be enforced to apply the new preprocessing steps as well. The following figure (carved out from the book) illustrates such pattern, in the context of predicting the duration of a New York City Citibike ride:

There are cases in which one can not package the input-to-feature transformation in the model. For example, in the above bicycle duration prediction model, if a feature is “the hour of the day for the previous bike ride from the same station”, obviously we need to treat it as a raw input instead of something we can “transform”. For such cases, the Feature Store design pattern discussed later would be a better approach.

Bridged Schema

This design pattern aims to address the issue when the training dataset is a hybrid of data conforming to different schema. Assuming that we are training a regression model, and one of the (categorical) inputs is called payment_type. In the older training data, this has been recorded as cash or card, However, the newer training data provide more detail on the type of card (gift_card, debit_card, credit_card) that was used. During inference, we are expecting the detailed input as well. How to handle the different schemas?

There are two simple solutions, none of which seem to be optimal. One can either discard the older training data, or roll up the newer training data (and for inference) by treating all three different types of card payment as card. For the first approach, we lose the training data, and for the second approach, we lose the information hence degrading the model performance (need to validate!). Is there a better approach?

This is where the Bridged Schema idea comes in. The main idea is that, can we find a representation (schema) for the input (in this example, payment_type), that works for both the older and newer data?

Probabilistic method

With this approach, we effectively “impute” the older data. When we see a payment_type == card in the order data, we convert it to one of the (gift_card, debit_card, credit_card), with the probability of the observed frequency in the newer data. The assumption here is that the distributions of the imputed input are the same for the older and newer data, which may not hold.

Static method

With this approach, we one-hot encode the input using the newer data. For the running example, the payment_type is one-hot to a 4-dimension vector, as the cardinality is four (for newer data). When we encounter the payment_type == card in the older data, we will represent it as [0, 0.1, 0.3, 0.6], where the first 0 corresponds to the cash category, and (0.1, 0.3, 0.6) is the hypothetical, observed frequency of (gift_card, debit_card, credit_card) from newer data. Comparing with the probabilistic method, we relax the “same-distribution” assumption, but allow the ML model to learn the relationship.

Union schema method (don’t use)

Similar to the static method, one could propose to set the cardinality of the payment_type to five, that is, treating card as its own category. Although tempting, this approach is problematic, since we will never see payment_type == card during inference.

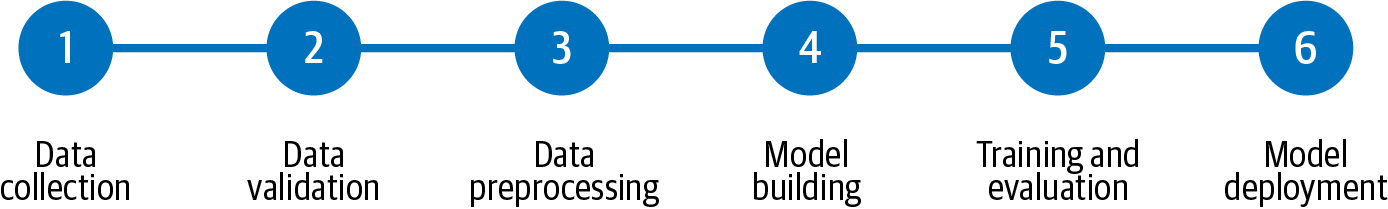

Workflow Pipeline

As an ML practitioner, we can often find our daily routine following some or all of the steps outlined in the figure below.

Similar to the recent monolith-versus-microservice discussion in the traditional programming domain, the Workflow Pipeline design pattern aims to isolate and containerize the individual steps, that turns the ML codes to pipelines. Such pattern will ensure the portability, scalability, and maintainability of the ML codes. It is particularly important when we are working in a team, for example, different members can retrieve data from a common, immutable source to train their own models, so that the results can be compared on an equal footing.

Another benefit of abstracting and isolating individual steps is that, one can insert validation between steps, to monitor the quality and status. Should there be data drift, or model quality degradation, it would be easier to identify and faster to remediate.

Tools to implement such pipelines include Apache Airflow, Google TensorFlow Extended, and Kubeflow. However, to practice this pattern requires solid infrastructure support, as it is most likely one needs to run and maintain those pipelines with some cloud providers.

Feature Store

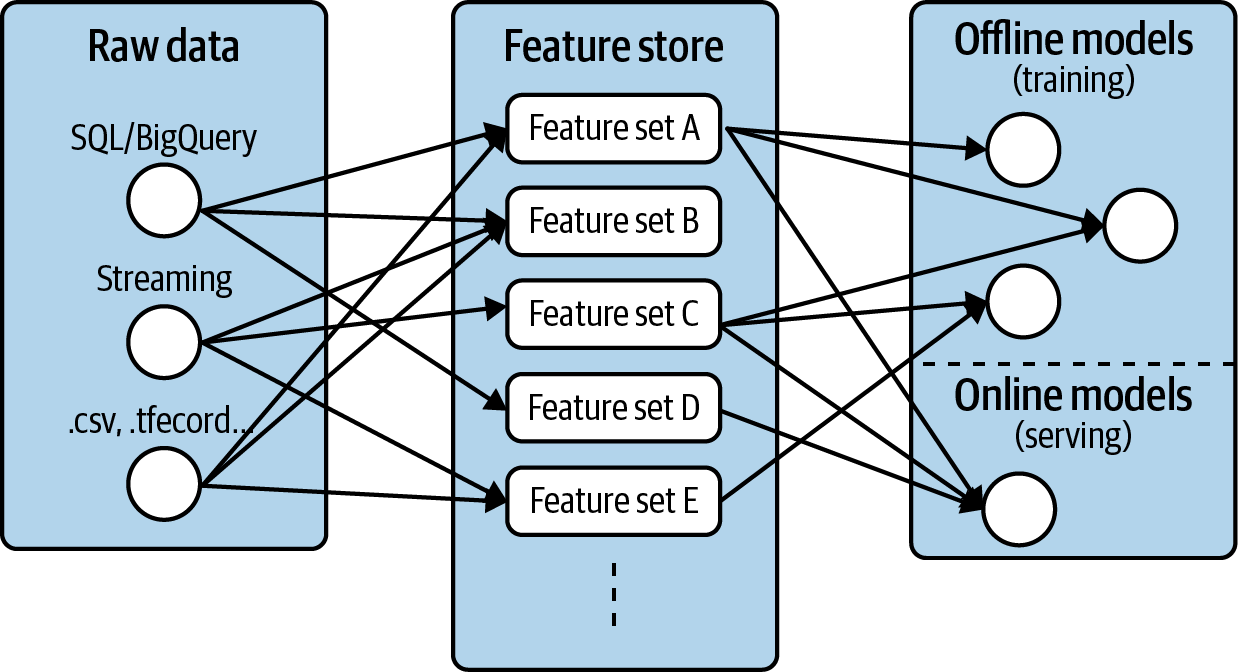

This design pattern intends to address the maintenance and sharing of the most crucial component in ML – feature. At the high level:

The Feature Store design pattern simplifies the management and reuse of features across projects by decoupling the feature creation process from the development of models using those features.

Here the boundary between input and feature can be a bit blurry, but it would not affect the content we are discussing below.

There are at least two issues that feature store wants to solve: training-serving skew, and feature-sharing. To address the former, one needs to ensure: 1) the feature generation processes are identical for both training and serving data; and 2) the features are available at serving time with low latency. For the latter, one needs to expose the location of the features for other members/processes to ingest.

One would argue the indifference between the Transform pattern and this Feature Store pattern. Indeed the Transform pattern would enforce the consistency of the feature consumed by the model at training and serving time, but the Feature Store pattern is to provide the availability of input/feature for training and (particularly) serving. Furthermore, certain types of feature (e.g., recency) can not be handled through the Transform pattern, and Feature Store is the more appropriate solution.

All these are easier said than done, but again there are tools to help, such as FEAST, and AWS SageMaker Feature Store. The book goes into depth with FEAST, and as with the Workflow Pipeline design pattern describe above, one needs to have ML infra support in place to properly enable Feature Store.

Other design patterns

In the above, I’ve only collected the Reproducibility design patterns that resonated strongly with me. There are other patterns discussed in this chapter, including:

- Repeatable Splitting: it captures the way data is split among training, validation, and test datasets to ensure that a training example that is used in training is never used for evaluation or testing even as the dataset grows.

- The Windowed Inference: it ensures that features that are calculated in a dynamic, time-dependent way can be correctly repeated between training and serving.

- Versioning of data and models: it is a prerequisite to handle many of the Reproducibility design patterns.

Overall, each of the design patterns is worth of revisiting, especially after one has encountered similar situations at work. For now, I will keep reading the rest of the book!

Leave a Comment